I got to thinking last time I read Jane Austen’s

Emma that it made a pretty good mystery story, with clues everywhere embedded, and Emma possibly the world’s most bungling sleuth (not even barring Inspector Clouseau).

|

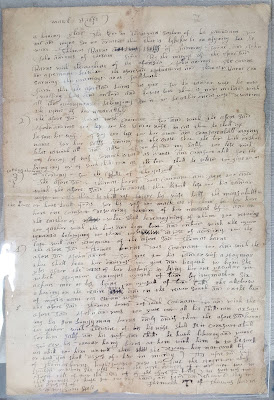

"I planned the match from that hour"

Watercolor by C.E. Brock, 1909 |

The novel opens with Emma claiming credit for the Taylor-Weston marriage. She falls onto the idea of matchmaking as a job for herself much as Lord Peter Wimsey decides to take up detecting things as his way to cope with post-war shell shock, though Emma has considerably less actual aptitude for her chosen hobby. Emma says to her father, “It is the greatest amusement in the world!” as if matchmaking were a party game. “And after such success you know!” she exclaims. As Mr George Knightly points out, Emma deserves no credit at all, beyond having the idea. “Success supposes endeavour,” he notes, and concludes, “you made a lucky guess; and

that is all that can be said.”

Despite Mr Knightly’s warning at the end of the first chapter that Mr Elton can take care of finding his own wife, Emma decides Mr Elton needs her matchmaking services. If Mr Elton’s romance life were a mystery, Emma would be the last sleuth to figure it out. She makes a friend of Harriet Smith and decides Harriet is the one for Mr Elton, despite Mr Knightly warning her further that “Elton will not do” for Harriet.

Here it is obvious that Mr Knightly and Emma have already shown clearly who is the superior at detection. When faced with the very same set of facts about Harriet Smith, the two could not disagree more in their conclusions. Mr Knightly declares that Harriet “is the natural daughter of nobody knows whom, with probably no settled provision at all, and certainly no respectable relations. She is known only as parlour-boarder at a common school. . . .” He denigrates her intelligence and concludes, “She is pretty, and she is good tempered, and that is all.” Emma, incensed at his judgment, rebuts him with her idea that Harriet is the daughter of a gentleman of fortune, suggested by Harriet’s having a liberal allowance, and therefore she deserves to marry a gentleman, a significant social step above the “gentleman-farmer” Mr Robert Martin who has just proposed to Harriet and been turned down at Emma’s instigation. But as Mr Knightly points out, Harriet has been given an “indifferent education” at Mrs Goddard’s and has been left in her hands “to move, in short, in Mrs. Goddard’s line, to have Mrs. Goddard’s acquaintance” except that Emma decided to make a friend of her. Mr Knightly correctly states that Harriet was happy with her social sphere until Emma decided she should raise her expectations. He is in his turn incensed at Emma’s interference in the Robert Martin - Harriet Smith romance.

This is the first case where Emma reads every fact wrong, makes every wrong conclusion, interprets what she sees, hears, and experiences with a total lack of understanding. If there were a dead body, she would have fallen over it and thought it something else without a second look.

The next case where she falls on her face over all the clues is that of Mr Elton’s romance. As with the Martin-Smith case, here she needs the help of a Knightly, specifically her brother-in-law, John Knightly. She has rejected Mr George Knightly’s understanding that Mr Elton will look for a well-connected and wealthy woman, and Emma has gone on imagining that every encounter with Mr Elton shows him falling in love with Harriet Smith. The episode of Emma’s drawing of Harriet, which Mr Elton begs to be allowed to take to London to have the likeness framed; the episode of Mr Elton’s contribution to Harriet’s collection of riddles and charades; the solicitude Mr Elton exhibits over Harriet’s being confined at home due to illness; all appear to Emma to be evidence of his attachment to Harriet Smith.

Then comes the episode of the Westons’ dinner party, which Harriet cannot attend and which Emma tries to get Mr Elton to excuse himself from attending, in vain. The narrator notes that Emma has been “too eager and busy in her own previous conceptions and views to hear him impartially, or see him with clear vision” until she is alone with John Knightly, and because he has observed Mr Elton and her interaction, he says to Emma that he thinks Mr Elton is partial to her and that she appears to be encouraging him. She laughs it off outwardly but considers John Knightly’s words throughout the evening of the dinner-party, and she cannot be completely taken by surprise when Mr Elton proposes to her in the carriage on the way home, although she keeps her head and plays her part convincingly, hoping in spite of all the evidence that Mr Elton really prefers Harriet and maybe is just drunk enough to behave badly. But of course she knew the truth after John Knightly pointed it out; she is prevaricating when she says to Mr Elton, “I have been in a most complete error with respect to your views, til this moment.” She thinks to herself just a moment later, “to Mr John Knightly was she indebted for her first idea on the subject, for the first start of its possibility.”

And the upshot is that Mr Elton is so offended by Emma’s behavior and especially by her having assigned him the role of lover to Harriet Smith, “the natural daughter of nobody knows whom” with no fortune or respectable connections, that he and, as soon as he marries, his snobby, wealthy wife miss no occasion to snub Harriet and wound Emma thereafter. Their snub of Harriet at the ball, and Mr George Knightly’s coming to Harriet’s rescue, leads to Emma’s finally gaining some degree of true insight. But that must wait until the mystery of Frank Churchill and Jane Fairfax is well underway.

Without even having met Frank Churchill, Emma has always meant herself to be his chief flirtation, and that is what happens when he appears. But before he makes his first appearance, she and Mr George Knightly have an argument about his character. Emma misjudges him and Mr Knightly comes very close to nailing his true character. He is weak, Mr Knightly insists, because he has not obeyed a strong social duty of the time, to pay a visit to his father and new stepmother to mark the occasion of their marriage. Indeed, three months passes before the news is shared that he is to make the visit.

The argument is the very interesting division between nature and nurture, with Mr Knightly arguing that the young man’s nature should have overcome any spoiling done by his upbringing, and Emma arguing that the upbringing could produce conditions of habit and thought that prevented his ability to perform the social duty. Nowadays we recognize a greater claim to Emma’s argument, but in those days, Mr Knightly’s views were prevalent. Frank Churchill is condemned for having neglected visiting the new bride, but everybody except Mr Knightly forgives him for it. Nevertheless, all contemporary readers would have known Jane Austen meant Frank’s weakness to be his own choice.

Nobody notices the clue that Jane Fairfax’s arrival in Highbury coincides with Frank’s letter announcing that he is coming.

Before Frank comes, before even Jane arrives, Emma introduces her prejudice against Jane Fairfax to Harriet Smith. A letter from Jane announcing her arrival is received by Miss Bates, who shares the news of it with Emma and Harriet. Emma congratulates herself upon escaping having the actual letter read to them, but the more shocking revelation is Emma’s suspicion, based upon circumstances reported in Jane’s letter and repeated second-hand by Miss Bates, that Mr Dixon, the new son-in-law of the people Jane lives with, prefers Jane to his new wife. Emma has very little evidence to produce such a suspicion, but she makes the best of it. That it reflects no credit on the people involved is perhaps what attracts Emma to the theory.

Emma’s theory is immediately followed by the history of Emma’s and Jane’s interactions, or lack thereof, which shows the roots of Emma’s jealousy of Jane. We should be on our guard against Emma’s thoughts regarding Jane Fairfax, for they are not likely to be trustworthy. But this is Emma’s story, so the clues are buried again in our sympathetic views of Emma, despite everybody clear-headed (i.e., the Knightlys) being ready to point out all Emma’s faults and especially her misinterpretation of evidence.

Upon meeting Frank Churchill, Emma immediately detects him in a falsehood when he says that he was never able to indulge his curiosity to visit Highbury before, but she passes it off as merely a pleasantry. At the end of this visit, she fails to note the significance of the fact that he might have stayed longer—his father suggested it—but that he is determined to visit the Bates home and see Jane Fairfax.

As Emma shows Frank around Highbury the next day, she begins to notice what she considers are his deficiencies. He has a lack of proper regard for rank, she thinks, and he criticizes Jane Fairfax’s looks, which Emma cannot allow to pass, as Jane Fairfax is really very good looking. She fails to note the significance of his abrupt change of subject when she begins to inquire about his acquaintance with Jane Fairfax at Weymouth the previous summer. Emma fails to note that when he returns to the subject, it is when he has good command of what he will and will not say. She leads the way into her suspicions about Jane’s character, without fully committing herself as to what she suspects. “I have no reason to think ill of her—not the least—except that such extreme and perpetual cautiousness of word and manner, such a dread of giving a distinct idea about any body, is apt to suggest suspicions of there being something to conceal.”

Without realizing what she has just said, Emma thus succinctly sums up exactly what is the case: Jane Fairfax has a mystery to conceal, and Emma is completely wrong as to what it is. This is Jane Austen laughing at us readers. Back when Emma was reflecting upon how wrong she was about Mr Elton and how right the Knightlys were, she thinks, “There was no denying that those brothers had penetration.” It is the Knightly brothers who eventually reveal important clues about Jane Fairfax’s hidden truth.

Next Frank goes to London to “get his hair cut”—but really to order a pianoforté anonymously for Jane Fairfax. The news of the instrument comes at the Coles’ dinner party, which Emma, with all her class-consciousness, has condescended to attend. Nobody connects Frank’s crazy day-long trip to London with the arrival of the pianoforté. Not even Mr Knightly. Emma and Frank discuss the matter during the dinner. Emma again speaks ironically: “One might guess twenty things without guessing exactly the right; but I am sure there must be a particular cause for her chusing to come to Highbury instead of going with the Campbells to Ireland.” Of course there is. Jane does not want to be so far away from her secret fiancé. That secret fiancé, in turn, speaks truly when he says about the pianoforté, “I can see it in no other light than as an offering of love.” Emma has injudiciously admitted her suspicion that Mr Dixon loves Jane Fairfax, and Frank uses that as his cover in stating the exact truth.

When Frank comes to say good-bye to Emma on the morning of his return home to Enscombe, Yorkshire, she fails to connect his very low spirits with his having come directly from saying good-bye at the Bates house. Instead, she interprets his manner and words as tending toward a declaration of love for herself, which she intends lightly to discourage and ultimately to turn down.

A comic interlude introduces the new Mrs Elton to the society of Highbury. After enduring Mrs Elton’s first visit to Hartfield, Emma is incensed at her behavior and attitudes. She wonders what Frank Churchill would have thought of her, thinking to herself, “Ah! there I am—thinking of him directly. Always the first person to be thought of! How I catch myself out! Frank Churchill comes as regularly into my mind!” But first she had been thinking of Mr George Knightly, then Mrs Weston, and then Harriet, before Frank Churchill came into her mind, so she is ironically incorrect. It is most interesting that Emma has no trouble in interpreting the evidence of Mrs Augusta Hawkins Elton’s manners and speeches, and of assessing her character correctly. When a character has no possibility of a match to make, Emma is apparently capable of clear discernment.

At Emma’s dinner party for the new bride (Mrs Elton), Mr John Knightly discovers that Jane Fairfax hurried through the rain that morning to the post office for the mail. The news goes around all of the guests present, and Jane is taken to task for risking catching a cold. She protests that there was very little rain yet, and she reveals her adamant intention to continue to pick up her own letters, over the nearly-equally strong-willed Mrs Elton who wants her servant to run the errand for Jane in future. Jane cannot allow this—for Jane must have access to the post office to send and receive letters from Frank Churchill, a deep secret. Letters between unmarried people meant there must be a positive engagement to be married, or a very serious scandal.

Soon after this, Frank returns to Highbury, spends a quarter hour visiting Emma, and leaves to rush to Highbury to see “acquaintances” he saw on the street. As there has been no mention of his having formed friendships with any other family but that of the Bateses, Emma should have wondered at his needing to go there so quickly. But she doesn’t.

Before the ball at the Crown Inn begins, Emma does not notice and interpret Frank Churchill’s extreme agitation about Miss Bates and Jane Fairfax and when they are to arrive. She doesn’t notice that he leaps to the door when their carriage is heard and is in time to make sure no rain fell on Jane Fairfax until she is safely inside. Miss Bates embeds that piece of information in one of her rambling and incessantly long commentaries on all that was happening, and she also embeds the clue later on when they go in to the supper that Frank takes Jane’s fur tippet and wraps it around her. Emma misses all these clues. The next day, when Harriet Smith and her friend Miss Bickerstaff are attacked by “gipsies” and saved by Frank, nobody notes that he had been at the Bates home to return a pair of scissors. It is a throw-away clue mentioned during Harriet’s great distress, so Emma misses it, as usual.

After this point the author allows us a look into Mr George Knightly’s consciousness. He is becoming very suspicious of Frank Churchill and Jane Fairfax. He observes looks between them. As all the principal characters meet in the road and walk together to Hartfield, Frank drops his bombshell blunder, asking Mrs Weston about something that Jane had written to him privately, and clumsily retreating into the fiction of its having been a dream. But Miss Bates is right there to reveal that she knew about it and had told Jane and the Coles, and nobody else. At Hartfield a number of them play the Alphabets game, and Mr Knightly sees Frank spell b-l-u-n-d-e-r for Jane to see, and “Dixon” for Emma to laugh at and Jane to be offended by.

Mr Knightly attempts to warn Emma that he thinks there is a stronger relationship between Frank Churchill and Jane Fairfax than anybody else has a clear idea of, but Emma rejects his view completely.

Then comes the Box Hill party, followed the next day by the strawberry party at Donwell Abbey. Frank’s moodiness is another strong clue, coming right on the heels of Mr Knightly’s warning, but Emma keeps rejecting evidence piling up all around her. Jane’s anger, too, is a clue. Frank’s flirtation with Emma, which she herself acknowledges has no heart, no real intent toward herself, she fails to look at with what should have been an obvious question: if he did not mean to secure her attachment, what then did he really mean?

Jane Fairfax adds to the pile of evidence by suddenly reversing her theretofore steady rejection of Mrs Elton’s attempts to find her a situation as governess in a good family. Emma does not find anything odd about the suddenness of her reversal. She does not connect it to her own and Frank’s behavior at Box Hill and Jane’s subsequent flight from the strawberry party. She does not connect Jane’s refusal of Emma’s offer of a carriage outing, or her refusal of Emma’s present of Hartfield arrowroot, with her recent conduct. She thinks her attempts at friendship have been rejected because of their shared history and her never having wanted to be friends with Jane. Emma fails to consider her own attempts at normal conversation had been met by nothing but polite reserve, if not downright prevarication that led her to complain to Frank Churchill that Jane lacked openness. No wonder she found Jane difficult to like! Jane Fairfax, all the clues proclaim, dislikes Emma as much as Emma dislikes Jane.

Emma admits to the truth of Mr Knightly’s early charge that she is jealous of Jane Fairfax, because in Jane she could see the excellence of accomplishment that Emma herself never practiced enough to attain. We can surmise that Jane in her turn is probably somewhat jealous of Emma for having so many advantages of wealth and position that she simply squanders in comparison to what Jane has. Then too, Jane’s future looks pretty bleak compared to Emma’s. Jane is looking toward a life of maintaining herself as a governess, something everybody in the novel apparently agrees is not a happy prospect. Emma herself expresses her pity for Jane’s future prospects. Even Mrs Elton, by her comment on the desirability of a situation in a family that allows wax candles in the school room, reveals the bleakness of the position of a woman born in a privileged class, but without money, being relegated to having the choice of wax over smelly tallow candles taken away from her. It is no wonder that Jane does not want the friendship of someone as shallow or capricious as Emma Woodhouse, with her big home with rooms where one could be alone if one wanted to, and her very own neglected pianoforté, and her unknowing tormenting flirtatiousness with Jane’s own fiancé, and her condescension and carriages and arrowroot.

|

| Watercolor by C.E. Brock, 1909 |

Emma herself has far less animosity toward Jane than Jane probably has toward Emma. When the mystery of Jane Fairfax’s secret engagement to Frank Churchill is revealed, beyond a short bit of censure for Jane having made a wrong choice to enter into the engagement, Emma’s main condemnation is for Frank’s actions. “I must say, that I think him greatly to blame. What right had he to come among us with affection and faith engaged, and with manners so

very disengaged?” Thus does Emma condemn first Frank’s attentions to herself. About Jane, she says that looking on all this behavior shows “a degree of placidity, which I can neither comprehend nor respect.” But she returns to Frank, saying, “It has sunk him, I cannot say how it has sunk him in my opinion.”

Mainly, Emma is indignant about something much more fundamental:

“What has it been but a system of hypocrisy and deceit,—espionage, and treachery?—To come among us with professions of openness and simplicity; and such a league in secret to judge us all!—Here have we been, the whole winter and spring, completely duped, fancying ourselves all on an equal footing of truth and honour, with two people in the midst of us who may have been carrying round, comparing and sitting in judgment on sentiments and words that were never meant for both to hear.”

Naturally part of Emma’s indignation is for her own conduct, for having voiced her groundless suspicions of the relations between Miss Fairfax and Mr Dixon to Frank’s too-receptive ear. “They must take the consequence, if they have heard each other spoken of in a way not perfectly agreeable!” But her open nature abhors a mystery after all. She wants no part of deceit and treachery, no espionage. Emma is not, by nature, a sleuth in any way whatsoever.

And yet this is another instance of the supreme irony of the entire story. For Emma herself has a secret that is unknown even to herself, and even more central to the novel than the mystery of Frank and Jane, is the revelation of Emma’s own true preferences to herself.

There are subtle clues throughout the first half of the novel, including Emma’s little speeches to her father and to Harriet that she never means to marry. As she explains to Harriet, she has everything she thinks she needs: consequence, wealth, and a home where she is essentially the supreme ruler. She admits that she has never been in love and that if she were, perhaps that would change the case. Mr Knightly, ever speaking the truth, says to Mrs Weston early on that he would like to see Emma in love and in doubt of its return. He thinks it would be good for her. Emma is destined to come to that state, but when Mr Knightly sees it, he does not recognize it for his wish. The greatest clues we have early on are the episodes when Emma and Mr Knightly clash in their opinions, and Emma comes away not liking to disagree with him and hoping to make up again.

It is a little over halfway through that the mystery of Emma’s feelings begins to clarify, and the problem of Emma’s inability to recognize proper evidence or to interpret clues is again used to comic effect. Mrs Weston suggests that Mr Knightly might be partial to Jane Fairfax, and Emma vehemently denies the possibility, though we know that this is only Emma’s wishful thinking, not based on solid evidence. And yet Emma is right: Mr Knightly does not love Jane Fairfax. Both Mrs Weston and Emma need to realize that Mr Knightly speaks exact truth, never meaning more than he says.

When Emma and Mrs Weston next discuss Mr Knightly and his behavior, Mrs Weston is more sure that he is partial to Jane Fairfax, and Emma is more determined that he cannot be. Emma has no idea that this is actually true. Neither she nor Mrs Weston interpret the clues correctly.

A few times in the novel, Emma compares someone to her ideal man, subconsciously each time describing Mr George Knightly. As she thinks of her possible future with Frank Churchill, which always consists of his declaration of love and her rejection of him, she unconsciously compares him with someone as yet unnamed in her consciousness, “I do not look upon him to be quite the sort of man—I do not altogether build upon his steadiness or constancy.”

The same sort of thing happens just before the ball when Emma thinks of Mr Weston, “to be the favourite and intimate of a man who had so many intimates and confidantes, was not the very first distinction in the scale of vanity. She liked his open manners, but a little less of open-heartedness would have made him a higher character.—General benevolence, but not general friendship, made a man what he ought to be.—She could fancy such a man.”

When Emma thinks that she thinks of Frank Churchill first in every thought, she actually has first thought of Mr George Knightly and has subconsciously defended him from Mrs Elton. “Insufferable woman! . . . Absolutely insufferable! Knightly!—I could not have believed it. Knightly!—never seen him in her life before, and call him Knightly!—and discover that he is a gentleman! A little upstart, vulgar being, with her Mr. E., and her

caro sposo, and her resources, and all her airs of pert pretension and under-bred finery. Actually to discover that Mr. Knightly is a gentleman! I doubt whether he will return the compliment, and discover her to be a lady. I could not have believed it!” This is not a passing thought for Mr Knightly, but something at length, reflecting the strength of her indignation and sense of wrong that this woman should immediately pretend to be more intimately a friend of Mr George Knightly than Emma herself. (Note that the use of a surname alone seems to denote some degree of intimacy that Emma never herself uses; a critic I read recently pointed out that such use was falling out of favor by the time

Emma was written, as compared to

Pride and Prejudice, where it is used extensively. In the time period that

P&P was written, ca. 1795 with revisions after 1805 until its 1813 publication, the usage mostly disappeared.)

When Emma and Mrs Weston are intent upon their misinterpretations of Mr Knightly’s opinions of Jane Fairfax, he says what should have been a clue to his real feelings: “Jane Fairfax is a very charming young woman—but not even Jane Fairfax is perfect. She has a fault. She has not the open temper which a man would wish for in a wife.” Lest Emma miss this clue, he repeats it at the end of their conversation: “ ‘Jane Fairfax has feeling,’ said Mr. Knightly—‘I do not accuse her of want of feeling. Her sensibilities, I suspect, are strong—and her temper excellent in its power of forbearance, patience, self-controul; it it wants openness. She is reserved, more reserved, I think, than she used to be—And I love an open temper. . . .’ ” Both Emma and Mrs Weston allow this clue to fly right over their heads. They concentrate on their opposite pet theories regarding Mr Knightly and Jane Fairfax.

Emma ignores her own dawning conscious admiration of Mr Knightly at the ball. She looks for him and sees him with those who would not be dancing—husbands, fathers, and whist-players—“so young as he looked!—He could not have appeared to greater advantage perhaps any where, than where he had placed himself. His tall, firm, upright figure, among the bulky forms and stooping shoulders of the elderly men, was such as Emma felt must draw every body’s eyes.” At this time Mr Knightly is around 38 years old, certainly not old, but not so young either, especially compared with the other young romantic interests in the novel: Mr Elton is about 25, and Frank Churchill is just 23. Emma herself is 21. For such a young woman to so admire a man 16 or 17 years her senior argues pretty strongly for an attraction, conscious or subconscious.

In their subsequent conversation, he offers her a bit of consolation for the Eltons’ rude behavior, and he admits to her that he was wrong about Harriet Smith’s intellectual capacity. “Harriet Smith has some first-rate qualities,” he says to her. “I found Harriet more conversable than I expected.” This conversation is capped by Emma asking him to ask her to dance, and their mutual observation that they are not brother and sister—“no, indeed” says Mr Knightly, and depending on the inflection the reader gives it, this may be another clue for Emma, but if so, she misses it.

After Mr Knightly has observed interactions between Frank Churchill and Jane Fairfax that convince him that they have a deeper relationship than anyone knows, he feels he must warn Emma, whom he thinks is becoming attached to Frank. Of course Emma rejects his warning, but it should have given her a clue as to his feelings about her, and had she been able to look more clearly into her own actions, she might have realized her discomfort stemmed from something more than shame at sharing a joke against Jane Fairfax with Frank Churchill. “She could not endure to give him the true explanation,” which concerned her silly fabrication about Jane Fairfax and Mr Dixon. She is more than ashamed of having told Frank; she holds Mr Knightly’s opinion of her so far above anybody else’s, that it becomes painful to contemplate having to confess a shameful act to him.

It makes her reaction to his scolding at the end of the Box Hill excursion all the more telling. He cannot bear to see her acting less than her true potential, and she knows she was very wrong in her treatment of Miss Bates. She cries all the way home, not even caring if Harriet, in the same carriage with her, notices. But Harriet does not notice, and Emma immediately seeks to repair the wrong by visiting Miss Bates the next morning.

The scene when she returns home from this visit is telling and full of clues, but again, Emma fails to interpret them correctly. Her father praises her for having visited Miss Bates, and Mr Knightly, on the point of leaving for a visit to his brother in London, pauses.

“Emma’s colour was heightened by this unjust praise; and with a smile, and shake of the head, which spoke much, she looked at Mr. Knightly.—It seemed as if there were an instantaneous impression in her favour, as if his eyes received the truth from her’s, and all that had passed of good in her feelings were at once caught and honoured.—He looked at her with a glow of regard. She was warmly gratified—and in another moment still more so, by a little movement of more than common friendliness on his part.—He took her hand;—whether she had not herself made the first motion, she could not say—she might, perhaps, have rather offered it—but he took her hand, pressed it, and certainly was on the point of carrying it to his lips—when, from some fancy or other, he suddenly let it go.—Why he should feel such a scruple, why he should change his mind when it was all but done, she could not perceive.—He would have judged better, she thought, if he had not stopped.—The intention, however, was indubitable; and whether it was that his manners had in general so little gallantry, or however else it happened, but she thought nothing became him more.—It was with him, of so simple, yet so dignified a nature.—She could not but recall the attempt with great satisfaction. It spoke of such perfect amity.”

Emma does not discern more than the “perfect amity” in this exchange. She thinks it means that she has “fully recovered his good opinion”—but then, because of Mrs Churchill’s death, comes the news of Frank and Jane’s secret engagement, and because of that, Emma seeks to console Harriet, whom she had been hoping had become attached to Frank Churchill with only one piece of nameless encouragement by Emma—but when Harriet reveals that she has become attached to Mr Knightly himself, Emma is shocked into full consciousness of her own bit of the truth.

“Harriet!” cried Emma, after a moment’s pause—“What do you mean?—Good Heaven!—what do you mean?—Mistake you!—Am I to suppose then?—”

She could not speak another word.—Her voice was lost; and she sat down, waiting in great terror till Harriet should answer.

The only reason for Emma to feel terror is that she has instantly discerned the truth: Harriet thinks she is in love with Mr Knightly and that she has some reason to believe he returns her feelings. Of course Harriet is completely mistaken, and being Harriet, as soon as she is removed from the vicinity and sees Robert Martin again, she is easily persuaded by the young man who is truly in love with her that she is still in love with him after all, so all ends well there. (By the way, Harriet turns out to be the daughter, not of a gentleman, but of a wealthy tradesman. More irony for Emma’s ideas.)

Emma has more clues to misinterpret: Mr Knightly’s behavior to Harriet has been to sound her out and see if possibly she could be in a state of mind and heart for him to encourage Robert Martin to try again. But Emma, unwilling to examine all the evidence thus far, considers only that Harriet has said that she feels encouraged by Mr Knightly’s interest, and Emma feels despair.

|

| Watercolor by C.E. Brock, 1909 |

When Mr Knightly returns, he thinks to comfort Emma in the aftermath of Frank Churchill’s engagement coming to light, while Emma thinks he wants to consult her about possibly marrying Harriet, and both of them misinterpret each other’s words and looks.

However, this is a love story, and so they go on to discover their mutually strong feelings for each other and all is to end happily after all.

But can they be truly happy?

This spoiled young woman loves to argue her opinions and hates to be proven wrong. This rather set-in-his-ways middle-aged man always counters her arguments with the fact that he has lived so much longer than she has that he has all the knowledge and experience on his side and therefore must be right. She never examines evidence that pertains to her own self until forced to do so. How will she like being forced to do so every time they have a disagreement?

He is usually clear sighted and pretty good at seeing into people’s character, even to the point of being right about people he hasn’t even met yet. But about Emma he is curiously blind for a very long time. About Emma he is no better at examining the evidence properly than she is about him. (I should have compiled a list of this evidence about him, but you’ll just have to trust me until you read the book again yourself—it’s there.)

And yet, he is willing to go to the trouble to investigate Emma’s position and to tell her when he finds that she has been right. She is willing—more than willing—to make up every quarrel, for she can’t stand not being on good terms with him. With two such natures, they will probably argue a lot, but they will always come to an amicable resolution.

Further than that, the evidence shows that Mr Knightly will promote Emma’s best self. Emma brings positive growth to Mr Knightly’s character: nothing is more telling than that he comes up with the plan for him to move into Hartfield to accommodate Mr Woodhouse, despite the very real sacrifice it represents for him.

I predict a rocky start to their marriage, but ultimately, they will prevail and have great happiness because they will have come through those rocky times stronger together.

But Emma had best stay as far from other people’s romances as she can. She has no talent for the detective work that good matchmaking entails.

****************************

The text I used for quotes is

The Novels of Jane Austen: The Text based on Collation of the Early Editions, by R.W. Chapman; Five Volumes; Volume IV

[Emma], Third Edition. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, n.d.